Update: Since found a much more in-depth presentation on this topic titled banding in games by Mikkel Gjøl.

Color Banding

Computers represent colors using finite precision – 24 bits per pixel (bpp) is standard today, with 8 bits for each of red, green, and blue. This gives us 16 million total colors, but only 256 shades for any single hue. This is typically not a problem with photographs, but the discontinuities between representable colors can become jarringly visible on gradients of a single color. This artifact is called color banding.

Space games often have dark gradient backgrounds and thus suffer from visible color banding. Games following in the tradition of Homeworld 2’s gorgeous vertex color skyboxes are particularly afflicted compared to games with texture art because the gradient is mathematically perfect and there is no noise to obscure the color bands.

Here are some screenshots from a few games showing the effect. Make sure to click through to the full size image and verify that the color bands are indeed typically only one bit apart (DigitalColor Meter on OSX is great for this). The color banding is easier to see in a dark room.

Homeworld 2 (R.E.A.R.M.) |

|

|

Obviously these games are still incredibly beautiful! I just wanted to point out that many popular games exhibit visible color banding despite the existence of well understood solutions. Color banding in Reassembly bothered me enough to fix, and I thought that the solution was simple and effective enough that it should be more widely known.

Dithering

As mentioned above, color banding is caused by 24 bit color being unable to perfectly represent a gradient – the limit of color resolution. We can increase color resolution at the expense of spacial resolution via a process called Dithering. Since we are just trying to draw a smooth gradient and don’t care about spacial resolution, this is great. Dithering takes advantage of the fact that a grid of alternating black and white pixels looks grey. Please read the wikipedia article for a full explanation, and see also Pointalism for an early application.

Bayer Matrix

There are a lot of fancy dithering algorithms but I chose to implement Ordered Dithering via a Bayer Matrix because it can be done efficiently in the fragment shader. The basic idea is to add a small value to every pixel right before it is quantized (i.e. converted from the floating point representation used in the shader to 8 bits per channel in the framebuffer). The idea is that the least significant bits of the color that would ordinarily get thrown out are combined with this added value and cause the pixel to have a chance of rounding differently than nearby pixels. Bayer Dithering takes these values from an 8×8 matrix which is tiled across the image.

I store the Bayer Matrix in a texture which I sample at the end of my fragment shader. Here is the code to generate the texture. Note that we enable texture wrapping and nearest neighbor sampling and are using a one channel texture.

static const char pattern[] = {

0, 32, 8, 40, 2, 34, 10, 42, /* 8x8 Bayer ordered dithering */

48, 16, 56, 24, 50, 18, 58, 26, /* pattern. Each input pixel */

12, 44, 4, 36, 14, 46, 6, 38, /* is scaled to the 0..63 range */

60, 28, 52, 20, 62, 30, 54, 22, /* before looking in this table */

3, 35, 11, 43, 1, 33, 9, 41, /* to determine the action. */

51, 19, 59, 27, 49, 17, 57, 25,

15, 47, 7, 39, 13, 45, 5, 37,

63, 31, 55, 23, 61, 29, 53, 21 };

GLuint tex_name = 0;

glGenTextures(1, &tex_name);

glBindTexture(GL_TEXTURE_2D, tex_name);

glTexParameteri(GL_TEXTURE_2D, GL_TEXTURE_WRAP_S, GL_REPEAT);

glTexParameteri(GL_TEXTURE_2D, GL_TEXTURE_WRAP_T, GL_REPEAT);

glTexParameteri(GL_TEXTURE_2D, GL_TEXTURE_MAG_FILTER, GL_NEAREST);

glTexParameteri(GL_TEXTURE_2D, GL_TEXTURE_MIN_FILTER, GL_NEAREST);

glTexImage2D(GL_TEXTURE_2D, 0, GL_LUMINANCE, 8, 8, 0, GL_LUMINANCE,

GL_UNSIGNED_BYTE, pattern);

Then at the end of the fragment shader add the scaled dither texture to the fragment color. I don’t fully understand the 32.0 divisor here – I think 64 is the correct value but 32 (or even 16) looks much better.

gl_FragColor += vec4(texture2D(dither_sampler, gl_FragCoord.xy / 8.0).r / 32.0 - (1.0 / 128.0));

That’s it.

It’s important that this happens in a shader where the full gradient precision is available – if you do it in a post processing shader reading from a 24 bit color buffer it won’t work. In Reassembly I actually do it in two different places – in the tonemapping shader which reads from a floating point render texture and in the shader that draws the Worley background.

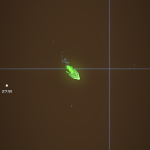

![[Reassembly]_Screenshot_(20140808)(03.59.40.AM)[606x500]](http://www.anisopteragames.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Reassembly_Screenshot_2014080803.59.40.AM606x500.png) Background halo with color banding |

![[Reassembly]_Screenshot_(20140808)(03.59.59.AM)[606x500]](http://www.anisopteragames.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Reassembly_Screenshot_2014080803.59.59.AM606x500.png) background halo with dithering |

![[Reassembly]_Screenshot_(20140808)(04.00.35.AM)[606x500]](http://www.anisopteragames.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Reassembly_Screenshot_2014080804.00.35.AM606x500.png) shield with color banding |

![[Reassembly]_Screenshot_(20140808)(04.00.45.AM)[606x500]](http://www.anisopteragames.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Reassembly_Screenshot_2014080804.00.45.AM606x500.png) shield with dithering |

![[Reassembly]_Screenshot_(20140808)(03.59.40.AM)[606x500]](http://www.anisopteragames.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Reassembly_Screenshot_2014080803.59.40.AM606x500.png)

![[Reassembly]_Screenshot_(20140808)(03.59.59.AM)[606x500]](http://www.anisopteragames.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Reassembly_Screenshot_2014080803.59.59.AM606x500.png)

![[Reassembly]_Screenshot_(20140808)(04.00.35.AM)[606x500]](http://www.anisopteragames.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Reassembly_Screenshot_2014080804.00.35.AM606x500.png)

![[Reassembly]_Screenshot_(20140808)(04.00.45.AM)[606x500]](http://www.anisopteragames.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Reassembly_Screenshot_2014080804.00.45.AM606x500.png)